Losing a spouse is like losing half of your own self, forcing you to learn how to live again, believes Jane Rocha, 67, widowed persons director at the YWCA of Southeastern Massachusetts.

She went through this process herself, after her husband died in 2018.

“Because my husband was chronically ill, my life became totally centered around him,” she said.

“It wasn’t just trying to put one foot in front of another for me, it was helping him put his feet one in front of another,” she continued. “When he passed away so suddenly, I was trying to take the two halves of myself and become one. I thought I don’t have to breathe for him and me anymore. I just have to do that for me.”

When Rocha speaks about relearning how to live your life, she means it literally. She and her husband had a standing Friday night shopping excursion, for example. Every week, they visited BJ’s and then Market Basket, where Rocha’s husband would get a coffee, while she shopped.

But after he died, Rocha wasn’t sure if she could make the trip alone.

Her first Friday at Market Basket was traumatic. She remembers spilling potatoes across the floor and nearly breaking down when a large man approached her to help collect them. He could see she was upset and at first thought it was his unfamiliarity and large size that caused her dismay.

What he said next made Rocha catch her breath.

“He said I used to sit with your husband at the counter and I just was so concerned because I haven’t seen him in a while. Is everything OK?” said Rocha.

The connection and timing of the moment amazed Rocha.

“I had never noticed him,” she added. “I’m in the store thinking, how do I get through this today? And that was how I got through that day.”

“It just was such a beautiful moment. I hugged the man.”

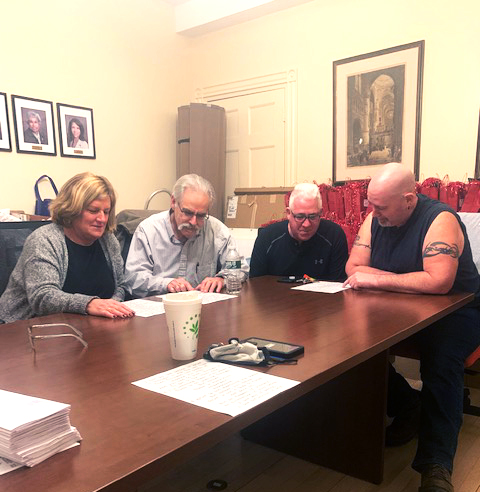

It’s been three and a half years since Rocha’s husband died, and during that time, she’s been learning to rebuild her life one step at a time. She now also works with other widowed people helping them grieve in groups run by the YWCA and at the Dartmouth Council on Aging.

Group meetings kick off with introductions. Everyone gets a chance to say who they are, introduce their loved one who died, and tell the group a bit about their own story. The conversation starts naturally from there, Rocha said, and she lets the group set the agenda.

It’s not hard to start conversations, she adds laughing. It’s much harder to stop them. She has even stopped calling for bathroom breaks because the group doesn’t want to stop, even for a minute.

Rocha’s experiences with grief, both messy and transformative ones, are helpful to those in her group, mainly because she serves as a benchmark for them, especially the newly widowed, she said. They can see where she is emotionally now and that gives them faith they can get there too.

“I did the work and that’s what I urge people to do,” said Rocha. “We all need healing in our lives. ”

She’s clear she’s not just speaking about women. Her groups now have more men than women, she said. “I’m as surprised as everybody,” she said. “Because men typically don’t talk about their feelings and men don’t volunteer to speak up in any type of a group session.”

But not true in Rocha’s group.

“I have male-dominated groups and they’re open, and they share, and they’re grieving openly. They cry. I don’t always have enough Kleenex on the table and that blows my mind.”

Although Rocha’s groups are not designed specifically for older adults, her perspective on aging today informs her work.

“As I get older myself, I see the disconnect between the generations. I think we have to fight for our lives if we want to stay mentally well and healthy. And I think seniors need to be taught how to do that because (so often) we don’t want to impose and we don’t want people to feel obligated,” she said.

“It’s a chronic issue where older adults feel invisible and they don’t feel heard and they don’t feel people want to be around them and it’s very, very sad.”

“How do you communicate that need to be able to connect?” she continued. “On the far end, where I am, it’s like I just see (older) people relegating themselves to the corner and they don’t need to do that. They’re still vital. They still have so much to offer. They need help in getting there.”

Beyond age diversity, Rocha also sees a world hit by the pandemic and struggling to figure out how to grieve.

“It’s almost a shame that it’s only for widows,” she said about her support group. “Because I think we need help grieving in society today. We don’t grieve well; we don’t connect; and we don’t stay connected and that adds to (the isolation).”

Recent Comments