November is National Family Caregiver month and to mark the occasion, Senior Scope spoke to both family and professional caregivers about the burdens and joys of caring for family members. We also asked them what helped them the most and what resources they might recommend to others.

What they told us reflects their unique situations based on family member’s needs, geographic and economic situations, and cultural and social expectations about care.

Some caregivers quit their jobs to provide care. Others retired or were already retired. Still others continued to work full or part-time. Some were young when caregiving was needed, while others were already at the age to be eligible to receive care themselves.

All struggled with some part of caregiving, from the demands of ongoing care, the responsibility of making decisions for another human being, and conflicting family beliefs on what good care is, to meeting other life demands including work, children or other family members and, usually farther down the list, themselves.

Here are some of their reflections on family caregiving today.

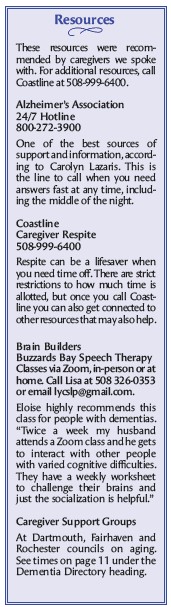

Both a family and professional caregiver, Carolyn Lazaris has worked with caregivers as a former Coastline options counselor, has provided care to both of her parents, and now leads caregiver support groups in the region and offers companionship services.

She left her job when her father needed care while in his 90s.

“I was spending all my day telling caregivers that you need to take care of yourself and then I’m racing home and I’m up five, six, and seven times a night with him,” she said about her decision. “I thought this feels really hypocritical.”

Her family was fortunate, she said, in that her dad had help coming into the home. Most families, Lazaris said, don’t have this level of outside care because it’s too expensive. It’s one of the reasons why she believes that respite time, provided by outside caregivers to relieve family members, is so important.

“It is one of the toughest things that you’ll ever do,” Lazaris said about caregiving. “You know how much you love the person, but you’re human. For some caregivers, your lives are turned upside down.”

“Caregivers aren’t looking for time every single week, but if there was something that could give them four to five hours a week and be guaranteed, so that you knew when your friend said, ‘Do you want to go out?’ That you could say yes,” she said.

As it stands now, Coastline provides respite for four hours a year to caregivers, said Personal Care Assistance Program Director Ana Hayes, although remaining ARPA funds have temporarily augmented that number. The real power behind the program, Hayes said, is the resources the organization can connect caregivers to that indirectly offer respite by helping the loved one in need of care. That’s done via an initial conversation between the caregiver and Coastline and an in-home assessment process.

“That’s the extra benefit about the caregiver program,” Hayes said. “We can come in, do an assessment and see what the caregiver identifies as their greatest need, or their goal, and provide some respite and link them in to a resource that might be beneficial to them.”

Dartmouth resident Diane Nunes and her siblings cared for their dad from his diagnosis of dementia, working to keep him living independently as long as possible. Like others, Nunes said her family initially thought the small difficulties her dad was experiencing were due to normal aging. But then an incident when her dad, then 85, traveled to Canada on his own and was unable to find his way out of the airport to meet the family member waiting for him, led to a diagnosis of dementia.

“He got off the plane and was wandering around. I don’t know if it was an hour or more before he figured out where to go,” Nunes said. “We didn’t know anything (before then). We thought it was just aging.”

One of the toughest aspects of her care experience were the personality changes her dad experienced. Nunes said her dad was always a mild, pleasant person. But when the family began making changes to keep him safe at home, he reacted angrily. “I was in tears,” she said. “I couldn’t believe he did that…That was a harsh reality.”

The family cared for him for three years at home with Nunes and her older brother, both retired at the time, taking the brunt of the work. Care eventually included sleeping overnight at the house when it became clear he could not be left alone.

In her search for resources, Nunes took a caregiver workshop and began going to a caregiver support group. Both were extremely helpful, she said.

“(The workshop) was wonderful because it showed me things I didn’t know…and how to handle certain situations that I wouldn’t have known how to do.”

Nunes also learned about New Bedford’s Social Day program and the family began sending her dad there for half days. “He didn’t like it but we made him go,” she said. “We just needed a break. Even though he didn’t like it, it was helpful for us… We did that for about a year and that was great.”

New Bedford resident, Eloise*, provided care for her father before he died and now, at nearly 80, is caring for her husband who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease and later, dementia. The two experiences have been very different, she said.

“As a caregiver there is a definite difference living with the person with dementia and also being almost 80 years old,” she said.

Her experience taught her how important it is to learn about the diseases a loved one has, including identifying classes and other support.

“That’s one of the most important things a caregiver can do is gain real knowledge of the disease so you can know how to talk to the doctor, what to expect and where to get help,” she said. “Number one would be to join a caregiver support group such as the one Carolyn runs; it is a life changer.”

The difficult parts of caregiving include a feeling of loneliness.

“You can get help from family and friends but at the end of the day, no one can take this huge responsibility from you. I find that I hold back sharing with friends because I don’t want to be a burden or a downer,” she said. “Just being in charge of every decision, large or small, financial, medical or house related can be stressful.”

*Editor’s note: Some caregivers chose to withhold their names for this article.”

Recent Comments