Far from home, with the world before him as a young college graduate, John K. Bullard turned his sails back towards his hometown of New Bedford, changing the course of his life.

Far from home, with the world before him as a young college graduate, John K. Bullard turned his sails back towards his hometown of New Bedford, changing the course of his life.

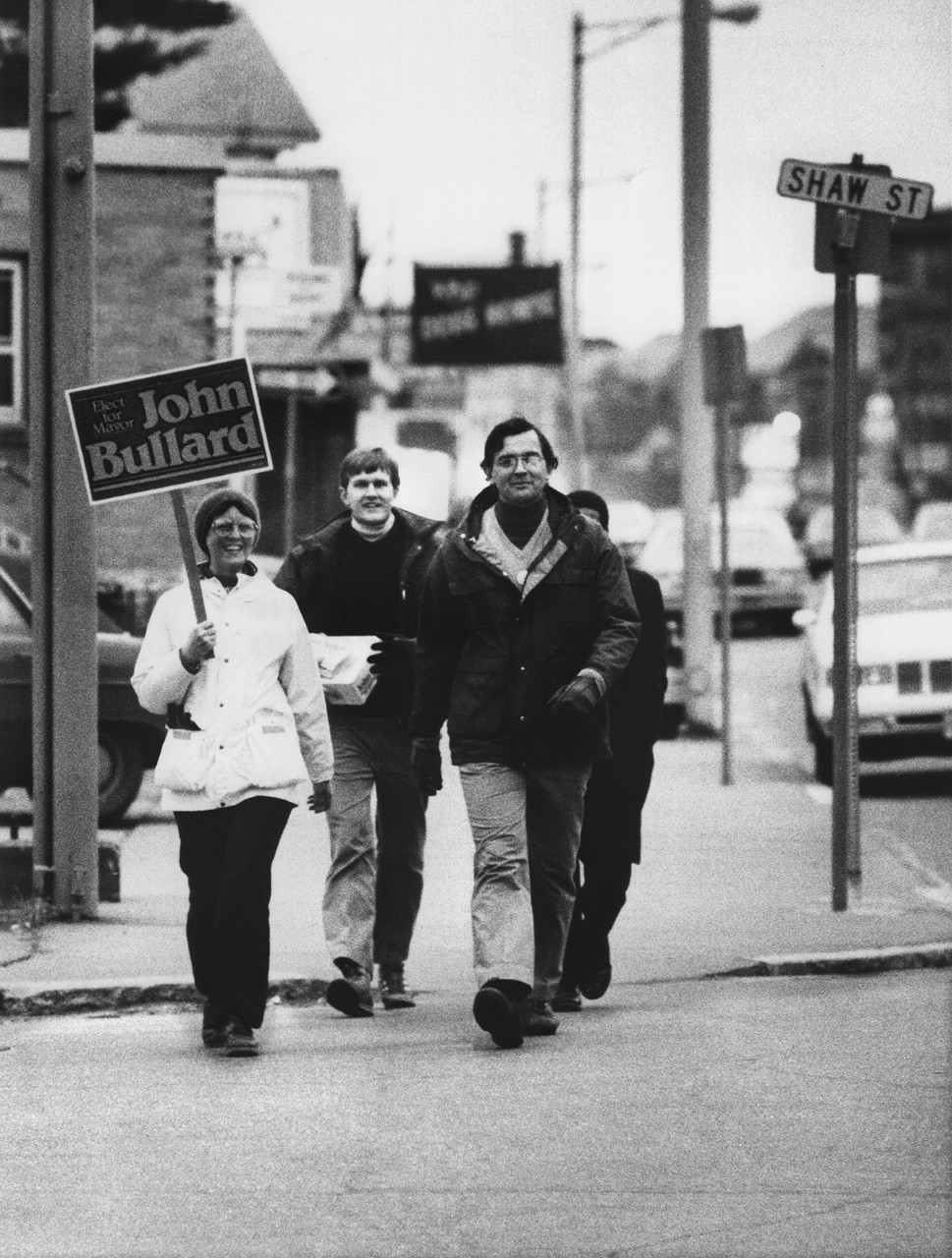

That’s an essential message in Bullard’s new memoir that puts New Bedford at its center and tracks the people and projects that helped revitalize the city through the eyes of a 13th generation son, longtime advo-cate, and mayor from 1986 to 1991.

Despite being born into an historic whaling family, with New Bedford roots dating back to 1765, Bullard was seeking a place to plant himself after college where he could help make the world a better place.

It was 1969, the world was in turmoil, and he had just graduated from Harvard.

On a journey that took him to Spain by “hitchhiking by sailboat,” he was inspired to stop resisting a life that felt prescribed — determined by the legacies of his ancestors — and instead embrace his heritage as an opportunity to make a difference by serving one small cobblestoned city by the sea.

The moment had such an impact on him that he starts “Hometown” by describing it in the book’s introduction.

“So much needed changing, and I wanted to be part of that change,” he wrote. “What occurred to me so far from home was that the best way to save the world was to focus on just one piece of it. And the best way for me to do that would be to work to make my hometown a better place.”

“What I had thought of as a path that someone else had laid out for me suddenly became my path,” he added.

In an interview in advance of the book’s release, Bullard said he wrote the memoir for two reasons. One was a lesson he learned from his grandfather to write down records of events for future generations.

“I want to recognize all of the characters who played a role (in New Bedford) and be certain that their work is honored and remembered,” he said. “I just want to get the record down.”

The second reason refers to the lesson that brought him back to New Bedford after college. Over the years, Bullard said, people have often asked him, ‘How do I have an impact? How do I save the world?’ In the pages of “Hometown,” he attempts an answer.

“I thought with this book, it might be a way to help young people answer this question,” he said. “There’s no one right answer, but it’s a very important question.”

In “Hometown,” Bullard tracks changes to the city, his professional career, and to his personal life. He and his wife, Laurie, who he dedicates the book to, have three children and five grandchildren.

Over a long career that extended far beyond New Bedford’s borders, Bullard worked for the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration, establishing the first federal office of Sustainable Development there and served as regional administrator for NOAA fisheries in the northeast. He co-founded the Southeastern Massachusetts Agricultural Partnership, the SouthCoast Learning Network, and the New Bedford Light. He serves as chair of the Westport Community Resilience Committee and is on the boards of the Buzzards Bay Coalition and the Westport Planning Board.

In all of his roles, he encountered numerous leaders, advocates, characters, and changemakers, all of whom make their way onto “Hometown” pages.

His highest praise is reserved for Sarah Delano, who he worked with at New Bedford’s Waterfront Historic Area LeaguE when he was in his 20s and she was nearing 80. Delano at the time was the historic preservation organization’s president, a role she filled from 1966 to 1982.

Bullard went to Delano when he learned the Zeiterion Theater was in danger of being torn down.

“She said, ‘let’s go take a look at this building,’” he said, about the woman who he described as defying the little-old-lady stereotype.

What they saw, Bullard said, was a theater that was falling apart, with missing seats, cobwebs, falling drapes, and peeling paint. “It was the most depressing sight you could imagine,” he said.

Delano’s reaction, however, was inspired — and inspiring. “She took it all in for about 10 minutes. We looked at each other and Sarah said you know, John, we’re going to have fun fixing this building,” recalled Bullard.

“That’s the key to how you age,” he added. “It’s that combination of optimism, courage and joy, that you don’t approach an obstacle or challenge with dread. You approach it with, ‘What an opportunity to have fun with somebody else, with other people.’”

“It’s all about the attitude you bring to it and the attitude is something you choose,” he continued. “That’s one of the many lessons I learned from Sarah Delano.”

“Here it is 45 years later and that building is bringing joy to everyone else,” he added. “She was 80 years old, leaping tall buildings with those tennis shoes. Was she constrained by age? I don’t think so.”

Bullard was working for the New Bedford Planning Department under then planner Ben Baker in 1970 when he decided to pursue a Master of Architecture degree at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. It was at MIT, he said, that he learned the value of curiosity and not knowing. It was a more chaotic environment than Harvard had been, he said, one which allowed for feelings of humility.

“When you spend any time at sea, you know you’re not the biggest thing around,” he said, in an attempt to explain the feelings. “You only exist with permission of a greater power.”

“You can’t be out on the ocean without being humble,” continued Bullard. “Then you’re going to be curious because you know you have something to learn. If you think you know everything, you don’t have anything to learn.”

That attitude served him well working on planning projects like strengthening Acushnet Avenue as a destination site and focusing on the deteriorating waterfront district.

Bullard used New Bedford as a focal point while at MIT. He petitioned the school to change his degree to a joint one in architecture and urban studies and planning, the first ever at MIT, to better suit his work in the city.

Although “Hometown” covers an extended period of time, Bullard doesn’t shy away from complicated current events. As one example, he spoke about his role as board president of the New Bedford Ocean Cluster, the organization focused on ocean economies including offshore wind and commercial fishing.

Here too, Bullard shows he believes empathy, listening, and being humble can help resolve conflicting interests.

“Most people see (the relationship) as totally confrontational,” he said. “But I believe that there is opportunity for both those industries to work together and to thrive together.”

It’s about being good neighbors, he said, adding that offshore wind has to listen to how turbine blades affect radar and other impacts on fishing habitats and fishing has to realize that fossil fuels have never been a friend of the fishing industry and the sooner we get on to clean renewable energy the sooner things are going to thrive in marine environments.

“Hometown” is published by Spinner Publications in New Bedford and available as of June 6.

Recent Comments